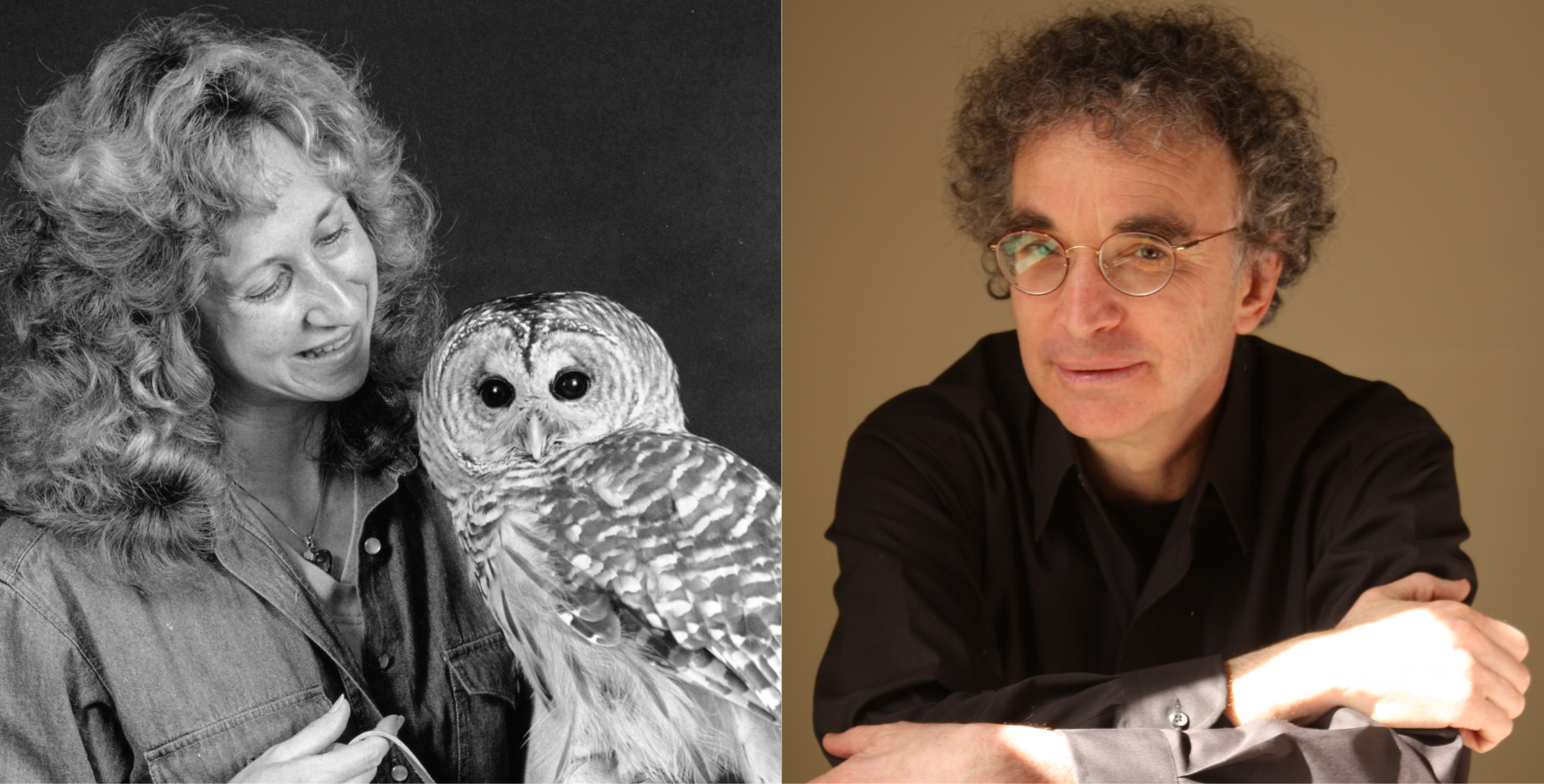

My neighbors, the NYTimes bestselling author Sy Montgomery and acclaimed author Howard Mansfield, have been married for 37 years. In that time, they’ve built and sustained a writing life that’s produced about 40 books between them. And even though they’re a unit, they’ve dedicated their lives to separate creative interests. Sy writes on behalf of animals — she’s best known for her books The Good, Good Pig and The National Book Award Finalist, The Soul of an Octopus — and Howard writes about architecture, preservation, and history in his quest to understand the soul of American places.

And while they live in the same home, they usually don’t know what project the other one is working on.That’s because they give each other the space, support, and feedback that each other needs to do their best work. In a rare combined media appearance, Sy and Howard share how we can treat the artists in our lives and model how to pursue our own creative efforts.

Takeaways

- Honor the artist in ourselves and in each other

- Create dedicated time for writing

- Provide useful feedback to fellow artists

- Repurpose work to find new ways to share stories, and

- Create connections through writing

Resources

Check out their websites: Sy Montgomery and Howard Mansfield

Follow Sy on social media: Instagram @sytheauthor and Facebook @symontgomery

Follow Howard on social media: Instagram @howardmansfieldauthor and Facebook @howardmansfield

Learn more about composer Ben Cosgrove

View Howard and Ben’s short film: “A Journey to the White Mountains”

Listen to my conversation with Liz and Matt Meyer Bolton of the SALT project

Transcript

This is Sy Montgomery. This is Howard Mansfield. And this is No Time to Be Timid.

Hey there, I’m Tricia Rose Burt and I want to ask you some questions. What creative work are you called to do but are too afraid to try? Is there a change you want to see happen in your community, but you’re waiting for someone else to step up and do it? Is fear of failure preventing you from starting new things that will make a difference to your life and to others? In this podcast, we look to artists to lead us and show us how they use creativity and courage to make changes in their lives and in the world. Pay close attention because this is no time to be timid.

Welcome to the show! As we mentioned in our last episode, I live in an area of NH that is rife with creative people and two of those creative people happen to be my neighbors — NYTimes Bestselling Author Sy Montgomery and acclaimed writer Howard Mansfield, a dynamic writing couple who literally live down the street from me. I mean I drive past their house everyday.

Sy and Howard have been married for 37 years and in that time they’ve built and sustained a writing life that’s produced about 40 books between them. And even though they’re a unit, they’ve dedicated their lives to separate creative interests. Sy writes on behalf of the animals — she’s best known for her books The Good, Good Pig and The National Book Award Finalist, The Soul of an Octopus — and Howard writes about architecture, preservation, and history in his quest to understand the soul of American places.

And while they live in the same home, they usually don’t know what project the other one is working on.That’s because they give each other the space, support, and feedback each other needs to do their best work. They’re a great model for how we can treat the artists in our lives and a terrific example of how to live our own creative lives.

In our conversation, Sy and Howard share how to:

- First honor the artist in ourselves and in each other

- Create dedicated time for writing

- Provide feedback

- Repurpose work to find new ways to share stories, and

- How to create connections through writing

By the way, this interview is quite the coup as Sy and Howard rarely if ever share media appearances. We met on my screened porch drinking tea and eating fresh strawberries as the hummingbirds flew around us. I’m so delighted you can join us for our conversation.

Sy and Howard, thank you so much for joining me here on the porch. Good to be here. Not a hard commute. OK, so I have lived down the street from you for the past 21 years. 21 years. Wow. Which means I’ve driven by or walked by your house numerous times every day. With different dogs. With different dogs. And you’ve had different dogs in your house as well.

And you have written more than 30 books. You’ve written nearly 20 books, is that right? I guess. Something like, I mean, an enormous amount of productivity since I’ve been driving by your house, basically. That’s the key to it, you driving by our house. I’m the secret to the success, thank you, right there. Okay. That’s it. But I wanna know,

how you’ve sustained this level of productivity. How have you created a writing life? I mean, I know y’all met each other at Syracuse. I think Howard hired you for the paper. He did. So you went into this marriage knowing we both write for a living. So it’s like, wasn’t a surprise. But how have y ‘all created a life that enables you to produce this kind of work? If I were to tell you why I love Howard, if you had many hours, the first thing…

would be I love his writing. I fell in love with his writing. And I fell in love with the writing long before I ever thought he’d like hold my hand or something. We wrote side by side in old Royal typewriters. Oh my gosh. And Sy smoked so many cigarettes she didn’t breathe. No way. You smoked cigarettes? She smoked like three packs a day. Easily. Easily.

I know it was incredible. She quit though, give her all credit for it. Yeah, yeah, I mean would have never imagined you being a smoker. She was a manic smoker. And I would drink Turkish coffee and then swallow the grounds. It was college. So that’s the key to how you’re sustaining this particular… That was it. No, that was it. No, the answer’s pretty boring. Writing comes first, you block off time for that, and you let nothing else invade that time. It’s a very boring answer, but it’s the truth of it. But that’s how…

we kind of honor each other. Yeah, because that’s the essence of what we do. I mean, I write to serve the animals, but writing is the way I serve them. And that’s why I draw breath. I mean, if I thought I couldn’t help animals, I’d throw myself off a bridge. And I love Howard for his writing. I know no one else who writes like that. He is the most creative, surprising lyrical writer I have ever ever met. And I know no one else who makes this deep connection with animals and what I’ve seen over all the years is that people catching up to Sy’s connection to animals. That’s what I’ve seen and she’s also my first and best editor. You know that’s amazing though to show each other your work. When I finish a chapter or an essay usually I’ll read it I read it to myself as I’m

going along, of course, aloud, but I’ll read it to her. And that’s when I know if it works or not. And essentially it’s done then. I mean, all the editing later, back and forth, but essentially the excitement or the enjoyment of creating it kind of ends about there. Yeah. yeah. That’s interesting. Yeah. And same with me. And, you know, my ears and tail will go down if he doesn’t like something, but I need to hear it. And we will tell each other, this doesn’t work.

Yeah. Well, if you don’t do that, then that’s just a waste of time. No, absolutely. You know, I mean, it’s I always ask the question, do you want a cheerleader or do you want feedback? There’s a very big difference between the two. And there’s times, you know, very early in a project when you probably do need a cheerleader. But by the time I hear Howard’s work and by the time he hears mine, it’s done. I am not going to bore him with twenty seven different, you know, edited versions of something.

Yes, same here. Yeah. And gosh, I often, I don’t even know what he’s working on most of the time until it’s finished. I never talk about what I’m writing because it’s, it’s, I can’t explain it until it’s done. So just there it is. He just disappears for hours and hours and hours and he’s working on Project X. Well, I have no idea what it is. But also though, don’t you experience that there’s sort of

there’s a magic, you sort of have to keep the project close until it’s kind of time to talk about it, because it dilutes the magic, I think, a little bit. I think for me, it’s a kind of song or kind of music you hear in your head and you’re trying to keep that to yourself while the rest of the world’s going, “my car’s got to get inspected, this has happened here, there’s something going on in the family.” And you’re just trying to keep that tune going in your head until you can get it out on the page. That’s the way I feel it is. What I also liked listening to you both say is that you read it out loud. Yeah, absolutely.

You know, I always read my work out loud. You both read your work out loud? Howard, you don’t usually like me to read mine out loud. I usually like to read it myself. Yeah, he reads it himself. But in the process of writing, do you say it out loud to yourself? yeah, absolutely. yeah, absolutely. Yeah, of course. Because you can hear it. You hear how it sounds. Yeah, it’s the most, yeah, it’s the best test. Okay, you’ve been in the game long enough, both of you, that you’ve had hits and you’ve had misses.

I can remember standing in the street with you, Sy. This was right after you had handed in The Soul of an Octopus to your publisher. And you had a couple of books that didn’t go as well as you had wanted them to. And you were like, this really, I need this to really work. And of course it did. I mean, you know, it was National Book Award finalist that kicked off this whole octopus

movement that’s been going on, I guess, for about a decade now. I think that’s safe to say. Octofrenzy. It is an octofrenzy. It’s an octofrenzy, absolutely. But how do you both, you know, how do you both get through those moments when you’re discouraged? Like if you had said, I’ve had two books, they didn’t work as well or whatever, one book that didn’t work as well, I’m just, you know, I’m done. Or how do you work your way through that to say, I’m going to keep going, you know, despite the fact I haven’t had all the validation I wanted right now?

Well, one thing is I know he believes in me. And the other is I consider, you know, our work, and by our work, I mean that of humans such as yourself, all creative people, you don’t know what’s going to be quote unquote successful or not. You don’t know if, who’s going to read this after you’re dead? You don’t know, you don’t get to see that.

It’s like a prayer. You don’t know how it’s getting answered. The important thing is to get it out there. And it’s, thank God I’m married to you. Because you get that.

Sy is how I’ve gotten through the really discouraging times because she’s always very positive. She’s the most sunny outlook person I’ve ever met. Pretty much you are. Yeah, I can. I can second that too, because you have held my hand when I’ve had some times. It’s like this is not working. That was dog stuff. Well, no, no, it’s also been creative stuff, too. And you know, when we were first together, you know, I had some rough years in and out of New York with different manuscripts and things that.

almost and not and publishers folding and just everything. It was sort of like you would open the door and fall down the stairs and you kind of hit a landing and you stand up and go, well, okay, we’ve learned, all right, all right. And then you take another step and you fall down the landing, you know, stairs again, it just went on for a long time. Just things not working, things being really close, but just not working. And so when did you get that sense of, okay, I got a rhythm now. What was the first thing that actually worked?

or that you felt that you considered worked that didn’t feel like you fell down the stairs? I don’t know. Well, the fact that we can keep working, you know, early on, okay, we got out of school, we graduated from Syracuse in 1979, we were not dating or anything. Analog era. Yeah. And I was working for a newspaper, he had a contract for a book right out of college.

And then I worked for the newspaper for like five years. I moved to Australia to live in a tent for six months and study emus on a hairy -nosed wombat preserve. And he moved. As you do. Southern hairy -nosed wombat. That’s right. I know there’s people just ready to at you about that. It’s a southern hairy -nosed wombat. It’s more endangered of the wombat. Let me ask you a question really quickly because I read about that. Stop that, you wombat haters.

I read about that and I was like, were you married to Howard at the time when you left for six months to go live in a tent? We were together eight years before we got married. Okay. Didn’t want to rush into things. Well, it was kind of like my heart belonged to you from the start anyway. But anyway. But that was a big deal also when we think about courageous things that you had a full -time job at a paper with a steady paycheck and said, I know, I think I’ll quit my job and live in a tent.

For six months. And then come back. And then come back. And we were both working without a net since like 1984. Yeah, you know, it’s like a roller coaster sometimes. You’re up and down. I’m familiar with that roller coaster. I think you are. I mean, I guess most people have sense enough to like marry a doctor or bank or something like that. But no, no. That’s our advice. No, it didn’t. Marry a hedge fund manager. You won’t see him. He could be at work all the time.

Just knowing, you know, that you’re going to make the time to do your life. You don’t know what your books or your articles are gonna do out there. But the fact that you keep doing it, that you’re able to keep doing it, that’s the success. Yeah, yeah. We had Liz and Matt Meyer Bolton on the show. Yeah. Yep, and I know that we’ll talk about them later, but they did a fabulous documentary on your piece with Ben Cosgrove. Yeah. And…

And Matt talked a lot about that. He was talking in terms of the Van Gogh painting, The Sower, and just said, that’s what we’re doing as artists and writers is just sowing seeds and we may or may not see the fruit of those seeds, but we sow them all the same. We sow them all the same. So some of the stuff that, you know, this is a practice I’ve done many times, if you have, as artists and writers, if we have material that didn’t necessarily work.

We repurpose it and I know that both of y ‘all have done that as well. Talk about that a little bit, Sy about how you’ve been repurposing some stuff lately. Wow. And there we have the birds in the background encouraging you to tell this. Yes.

The hummingbird’s up there. See him on that twig? Sorry, sorry. It’s okay. To our listeners, we’ve been sidetracked by a hummingbird. Keep going. Sorry about that. We’ve always kind of repurposed stuff just to make enough money. For example, you know, in the 80s, you would write a column for the Boston Globe. Well, there was no internet. So how would, and you would spend weeks researching this thing.

You know, we talked to everybody about whatever it was. You’d put in way more than $250 worth of effort and you’d have this one article that’s going to be on the bottom of the birdcage. Well, what do you do? You sell it to the LA Times because they are not competing. And then you rework it a little bit and you sell it to Animals Magazine. And that’s all gone now. That is all gone now. Because once it’s up online, it’s there. Everything is everywhere. However, there’s other ways. And at the same time, it’s nowhere.

Yes. There’s other ways to repurpose stuff, audiobooks, for example. Another is I did a book which was remarkably unsuccessful called Birdology. And that was not my title. The original title was Birds Are Made of Air. I know. So Birdology was a terrible title because people were turned off who thought it was too scientific and those who were scientific and know to know that it’s ornithology thought I didn’t know what I was talking about. The

bad paper, no color pictures, and the book did not do well and they didn’t give me a book tour. So of course it’s the author’s fault. It’s always the author’s fault. But let me ask you a question. Who came up with that title? Like how did you not get your title? This happens all the time. Even though your contract says that it must be mutually agreed upon, I must have come up with 20 titles for that book other than Birdology. I mean if it couldn’t be Birds are Made of Air, there was a bunch of others and they just kept saying no no no.

Oh geez. And basically they pushed me to the edge to, you know, guess what? We’re not going to publish this if we don’t get an agreement on it. And they pushed me until I said, well, I’m going to go to my grave hating the, I mean, anyway, nevermind. But the book wasn’t terrible. And I can tell you why, because years later, each of several chapters got republished as its own little book

with beautiful color pictures, with evocative titles, with gorgeous paper. And they’ve been like certainly regional and independent bookstore bestsellers. That’s fabulous. So exactly the same thing. And it’s also, you know, that’s kind of validating because I knew I didn’t write a terrible book. It was a good book. And then the third of that like little series of chapters,

sucked out of that book and made its own book is coming out this November. Which one is that? It’s called What the Chicken Knows. okay. But that’s a brilliant way of saying, I mean, you know, you helped me, both of you did when I was trying to work on that memoir that did not get picked up, but I have all of this content in there that’s good content and I put it in something else just because it was a lot of work for a lot of time. It didn’t end up where I wanted it to go, but it can be, it can go someplace else. Money in the bank. You know.

One hopes. We live in hope. You used to say that before the savings and loan crisis, if you’ve got to remember, when banks didn’t fail regularly. So now let me ask you, Howard, about you. You’ve adapted your work. Now, I mean, Sy repurposes her work. I’m sure you do the same. But I also want to talk to you about working with a composer with one of your books, because when did Chasing Eden come out? Boy, I’m thinking it came out right.

Covid was still going, was it 2021? I think we were at the tail end of COVID. Is that possible? COVID was March 2020. Hey, there it is. We can look it up. Yeah, and I have all of your, to our listeners, I have so many, I have a whole shelf in my home of just Sy and Howard’s books. Because we were making that decision, should it come out, should we wait another year. So it’s right, and we, because we did a lot of readings outdoors. You’re correct, 2021. 2021. So it was then, and

This is kind of hard to say.

People read books, but at the same time, the space for books in people’s lives is very narrow. They have a lot of things going on. They might be reading with the phone going by them, the TV on. So how do you get the words to stand up and have their own space? That we’re not being crowded out by just everything being everywhere. And I know Ben Cosgrove, he had come to talk to me. He had read my books when he was still in Harvard. Young guy, brilliant guy,

smart guy. And we had, we talked about the books and he went his way and I went my way. And we had a little correspondence and he disappeared. And then one day I get in the car and NHPR is on and I hear this kind of, you know, Saturday errands. I hear this piano music and I’m thinking, I like this. I like this music. Couple, you know, a hundred feet later, I know this music. It’s Ben. So I got back in touch with him and it was during COVID. And I said, you know, his music’s about landscape. It’s about moving across the land. It’s about what does this place mean to us? About how do we experience this place?

And so I said, what do we see if we can put your music together with one of my stories or one of my chapters? So in Chasing Eden, it’s a story about the White Mountains, how the artists come up to the White Mountains. They, and at the time, the White Mountains were considered to be a terrible wilderness. The artists come up there and have this transcendent moment and they make these huge paintings that people line up around the block to see. And then people get on the train,

and go up to stand exactly where the artist stood. The guidebook tells you exactly where to stand at what time and then these hotels are built and they burn and they get bigger and they burn and this whole thing sits. So right now at this moment, I swear to you, there are people standing right where those artists stood looking at those same scenes. They don’t know that’s why they’re doing it because they pulled out of their car and they’ve got their phone, but it’s the same thing. So that’s the story we tell in Chasing Eden in the show we did, which is about the White Mountains. And he would play and he’d pause and I would read.

And what I discovered, because I’m while he’s playing, I’m looking at the audience. I’m like, you know, I have a lot of time, too much time. You kind of get in the groove and you’re thinking too much. Stop thinking. Just wait, wait for your cue. But I could see people relax into it and I could see people suddenly hear the words that have been on the page for them all the time. Everything else is out of the room. I mean, this is a little pretentious to say, but it creates a meditative space for people. And they kind of dream along with it. I see people closing your eyes and people tell me that. And that’s why it works.

And the music is like a breathing space. I was in the audience. I got to see it at Kelly’s. You remember. remember. Yeah, yeah. You remember everyone who came. And all the ones that didn’t. No, but it’s just such an interesting, I mean, it’s just, you know, as artists, we’re always trying to figure out what’s another way people can hear what I’m saying. Exactly. That’s exactly what it is. You know, we’re constantly trying to figure this out. How do I put it in front of them that isn’t digital? Yes. That can actually…

enhance their souls. I mean, both of you are about connection, your connection with animals, your connection to place. It requires platforms that, you know, really enhance connection. OK, so what happened with the with the documentary, though? How did that did they come? They filmed you at the Concord, right? Yeah, the first show at the Capitol Theatre, the Salt Project, Liz Meyer, Liz Meyer Bolton and Matt Meyer Bolton and their crew came up and had like five cameras.

which is horrifying. But anyway, 5 cameras! So they filmed us and then the shows the shows about 50 minutes and then the TV show they made 37 minutes and 45 seconds, whatever it is that has to be to get on public TV. So she had to edit it. And she also – in the show, there are no pictures. There’s nothing because I didn’t want to become like an art history lesson. Sure. Yeah. Next line. Next line. Yeah. Anyway. So.

She came, Liz Meyer came up with adding historical stuff and footage as you would have to do. So it’s very different. OK, yeah, that’s very, that’s interesting. So there’s lots of images in there that were not included. And I we like the fact that there’s no images and people can just are free their dream. Don’t you don’t you like when you read a book, don’t you want to sort of imagine who this is telling you the story? Yeah. You know, and then you kind of sometimes you see the person on the back flap, you go, I don’t think so. Too bad.

No, but it is a way. I mean, I just loved the way that you were using and also collaborating with a composer, another artist, to create this whole other thing, this whole other experience. It’s fun to work with musicians, you know? Because he just hits the keys and people just melt. And sometimes we had one show where there was a Steinway grand that someone had donated in this big wooden room.

The sound was just amazing. I said, you know, Ben, you just you just play. I’ll be in the back. Who needs these words? Well, you know, It’s lonely. I find it. You all may not, but I find it lonely to work on my own, which is one of the reasons why I’m doing this podcast, because at least I get to work with Adam and then interview people who inspire me, because I find it hard to just be on my own all the time. It was hard when I was trying to write that memoir because I was by myself.

It takes a lot of courage to show up and do what y ‘all do on your own by yourself. You know, it’s it’s nothing more terrifying than a blank piece of paper. I think. No, that is true. I think we’re just lucky to do it. I’d rather do that than a lot of other stuff, you know, commuting with some job you hate. Or digging a hole.

Yeah, Sy doesn’t want to dig holes. Okay, now this is a perfect entree. I didn’t realize that Sy felt so strongly about digging holes. Oh, she does. This is a discussion about various house and yard projects that have to get done. I don’t want to be digging a hole. Okay, this brings me to, I was reading you had written something like a short autobiography for students, I think, who had been asking about the work that you do. And I have to read this. I love this so much. “When I was in grade school,”

This is what Sy included in her autobiography. “When I was in grade school, we had to fill out these questionnaires about what we wanted to do when we grew up. I was born in 1958 and grew up at a time when boys and girls were expected to enter different professions. So the form had separate columns. The girls’ choices listed things like mother, housewife.

teacher, nurse, and for the exotically inclined, airline stewardess. The boy’s side had stuff like airline pilot, doctor, and fireman. Neither column offered anything like climbing up Amazon rainforest trees in search of dolphins. Nobody suggested a career that involved being hunted by a swimming tiger in India, or searching for an unknown golden bear in Cambodia’s forest, or bathing in a swamp in Borneo while orangutans drink your shampoo and eat your bath soap.”

So,

I want to ask you, I mean, I just love that so much. What has it been like for you as a woman defying expectations, like from the start, like from the start you’ve been doing this? Well, you know what? I mean, this is the thing. I’ve never, when you talk about identifying as, you know, people talk about identifying as a boy or girl or woman or whatever. I, from the very start, did not identify as a woman or a man or even a human.

At the point that I could speak and could address this with my parents, I told them I was a horse. And my mother told the pediatrician in great distress and he said that I would grow out of it, which I did. That was when I realized I was really a dog. So I’ve never, I’ve never looked for mentors who looked like myself because I never identified with them. I identified with everybody else.

So my people are everybody who’s not people. And so I don’t think, I mean, I married a person and I have friends who are people, but. But we know where we stand. I’m just going to say very clearly. And also. Bringing up the rear of the parade. I guess, you know, I didn’t have time to feel like I don’t belong because I never thought I belonged to that group. You know, I always belonged. I always belonged with the animals and that’s where I am. And that’s where I am in my heart and in my mind and when I write.

We’ll get back to the second half of our conversation in a moment, but right now I want to tell you about our sponsor, Interabang Books, a Dallas -based independent bookstore with a terrific online collection. At Interabang, their dedicated staff of book enthusiasts will guide you on your search for knowledge and the excitement of discovery. Shop their curated collection online at interabangbooks.com. That’s Interabang, I -N -T -E -R -A- B -A -N -G books.com

It’s interesting because many of your books just have elements of memoir in them anyway, but I love…

I have it right in front of me. I want to make sure I get the title right. How to Be a Good Creature was particularly wonderful. And it is that your life memoir through animal, which was just really such a delight to read. And I’ve given it to a million people. That was not even my idea, that book. I didn’t want to write another memoir. I’d written a memoir of living with Christopher Hogwood, our wonderful pig who was 750 pounds.

I had the joy of knowing. You did know him. Yes. Not for as long as I would have liked because he, I think he left us. He was elderly when we met. He was elderly when I met him. And again, I stepped over a little bit. He was a 750 pound pig. Yeah, yeah. And then with razor sharp tusks, but he was a gentle soul. He came to us in a shoe box. Yeah, he was so little. No one thought he was going to live. He was the runt of runts that they didn’t have the heart to hit with the shovel on them. They knew we were pyons. So he came to us.

Yeah, he really exceeded our expectations. my God. Anyway, so I when after he died, I had to write a tribute to him. And so it was kind of like a memoir of my life with Christopher Hogwood But I did not want to write another memoir because I didn’t want to write about me. But How to be a Good Creature came about because I did an interview with a wonderful friend of mine, Vicki Croke, and she asked me about all kinds of animals. And at the

very end of the interview, she said, okay, so you’ve told me all kinds of interesting natural history stuff and a lot of adventure stories, but what have you learned from animals about how to live your life? And this was my answer. What I learned from them is how to be a good creature. That’s lovely. That’s really lovely. And the editor saw that online and said, you got to write that book. So I did. One of the…

One of the things I’ve also found interesting, and again in that short bio that autobiography wrote is, that book led to that book, and that book led to that book, and that book, and I think both of your lives shows like, just one project leads to the other project leads to, you know, work begets work, or begats, what’s the word I want here, work creates more work, creates more work, creates more work, you know, and I think that that’s, if we’re ever kind of floundering around going, I need an idea, often I find an idea in the work I’ve already done.

It’ll be the springboard for something else. When the student is ready, the teacher will appear. Howard, I want to ask you a question. You’ve come out with your latest book. I Will Tell No War Stories: What Our Fathers Left Unsaid About World War II. And your daddy was a gunner in World War II, correct? Yeah, and a bomber, yes. Yeah, yeah. And I want you to tell about how you came about writing that book because I think sometimes we overlook what might be right in front of us. Well, it’s completely by accident. In the last year of my father’s life, he lived to 94, but he was at home by himself with help. And, you know, things happen because this is the way this always happens.

So we finally convinced him to go to a home nearby, a VA home as it turned out. And I knew he’d been in the Air Force in World War II, but he never talked about it, which is a hallmark of that generation. So I knew that. As a little kid, I’d asked him some questions. He told me a couple of kid -sized stories about how good the English were, why we were there and everything. But nothing about combat, nothing about training, nothing.

So I opened up one drawer, we’re cleaning the house up, my brother and I, and he’s there, I’m there, and I can’t figure out what he’s doing, which I’m trying to clean the place up. And I opened up a drawer that had my father’s like tie clasps and cufflinks and stuff. A drawer I’d never be in. And I see this set of papers folded over and kind of lying in the corner. I pick it up, I open it up, and I realize it’s a diary of the bombing missions he flew when he was 19 and 20 years old in 1944. And I knew at that moment also,

from other things I’d written about the war, that this was strictly verboten You would not, they did not want airmen to do this because all information was highly prized. So I’m not standing, I’m reading it as if the ink is going to evaporate off the pages, you know. Each mission is described, you know, they’re flying back on three or four engines, they’re all shot up, they’re landing without brakes, the nose gunner’s injured, the flop is coming. I mean, it was like a movie, you know, page after page. And then I get to this dense block of typed text.

I pause, and it’s from the base censor. And there’s very military-ease saying, we’re seizing this, sign here and here, and we’ll mail it back to you after the war. Wow. Which, weirdly enough, they did. That’s such a miracle that they actually sent it back. 1639 Monroe Avenue in the Bronx. Yeah, they sent it right back to where his parents were living, where he came back to after the war. And so then he must have been in that drawer for 65 years.

So I thought, wow, you know, I really do want to know more about this. I’ll write for his service record. There are no service records. In 1973 in the Central Archives in St. Louis, there was a massive fire that burned for days. 40 different fire companies responded. And at the end, 85 % or more of Army and Air Force records from 1912 to 1960, gone. Nothing. The place looked like it had been bombed paradoxically. But I had that journal. I had his two Purple Heart papers.

And for some reason, and I don’t know why, I remember the name of his pilot who lived about 40 miles from us, but we never went to see him. But he was a car dealer, which is weird because we drove out that way, the East End, the Long Island. My dad liked cars. You know, I was a little guy let’s go see him. No. But his son had the same name, so I found him, you know, wrote him a letter, and he called me up and he said, you know, I have my father’s pilot’s log book. And from that, I was able to have the training in it, the name of the crew. And then from that, I was able to get from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

the actual planning for each mission, the teletype that went back and forth all night, thousands of pages, how many planes, how many bombs, here’s the code, what’s the weather, here’s the routes to fly, here’s the formations, back and forth all night long, and then coming back, did we hit the aircraft factory, did we not, do we have to go back, here’s the first intelligence, how many planes, did you see any parachutes, and then morale reports on the bases they were very concerned about morale.

We want to have a ping pong tournament, but we’re out of ping pong balls. What should we do? The kids were 19, 20, 21, 22. They were very concerned about morale. And it was a very strange way to fight a war, too. So from that, I was able to get a sense of what it was like to be a 19 -year -old kid out of New York in the air 20, 25 ,000 feet over Germany. And airplanes, by the way, that were not closed to the weather, were not pressurized. So it got to be 30,

40 below zero, they had these heated suits, they didn’t work very well. Frostbite was his first injury and he was treated for it his entire life. So you got a sense of the terror of that and what it was like and them being shot up from the ground by these anti -aircraft guns, tremendously shot up. It was fascinating. I think the story is amazing, but also the process of finding this just amazing gem. It was luck. It was luck.

Yeah, and I wrote it for my nephew because he’s about his early 30s because that’s the generation I thought needs to hear this, you know, not our generation. And I didn’t want it to be a very World War II -ish book. And I didn’t want it to be one of those books that’s about the armaments and about the hardware and about big battles with arrows on the map. I wanted to be, what did this feel like? And then why did these guys come back? And there’s women too who are WACS and WAVES.

Come back and not talk about it. And that was a code in that generation. That was something they held very close. I read one of the reviews of your, of the book and it’s, I don’t know if I have it written down here, but it was, they also didn’t want to re -enter the terror of it all. They just needed to just keep it at a distance. That was part of it. Part of it was we would never understand what it was. Yeah. But also, and most of all,

they did this for us. They went to war so we could live in peace. So don’t ask me about it. Just go live your lives. You’ll never understand. It was part of their service. I don’t know if that’s the best way to perceive, but that’s the way they perceived it. So I mentioned earlier, it’s funny because both of you…

you write about connection. Obviously, Sy with animals, Howard with place. You also have this sort of level of gentle activism, because you’re trying to change hearts and minds about how people are looking at things and experiencing things, which I love, because you’re not hitting anybody over the head, but you’re just sort of gently saying, let’s reshape things.

Yeah, it’s lovely. It’s a it’s, it seeps in rather than being hit over the head, right? It’s seeping in. And so you do have a quote that you had said, even when your confidence in yourself might fail, you can keep yourself going by confidence in your project and the message you want to convey and the thing that is bigger and more important than yourself. And so I’m

I want to ask both of you, what do you hope to accomplish with your work now?

I want people to understand that animals think and feel and know and treat them like creatures who think and feel and know and learn to live more lightly on this earth for them. I like that, live more lightly on this earth. I’d like people to realize how strange and miraculously ordinary is that’s all around them.

I want them to be more in the place that they are and open their eyes to it and realize the stories that are around them and the untold stories that are around them and to try and figure out why we tell certain stories and why we don’t. And just to realize how how odd it is just that we’re all here at this moment

I think even though y ‘all may be in different areas writing every day, you actually have similar missions in trying to show all of us things that we may miss. And we’re all the better for it, you know, to look at a mountain a certain way or to look at an animal a certain way.

So I love the image that I get to have every time I drive by your house, that you’re both at work doing these things. You know, Tricia you might just be doing email. I don’t think so. The occasional email. But though, really this commitment to making sure that we see things in a different way than we do. OK, here is my final question. I ask all of my guests, where do you need courage right now?

For me, we’re right in the midst of this enormous extinction. We’ve got global warming. It just seems like things are turning to dust in our hands and it’s so easy to feel hopeless and miniscule and hopeless. So…

What I do to find courage is I look to my mentors and my teachers who are the animals who are

brave and smart and endure. You look at turtles, turtles have survived the asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs. They survived the ice age. They might not survive us. But if you spend time with a turtle, this is a lesson in quiet persistence. You spend time with your dog who can see things that are real, but that you don’t.

You know, they can hear things that are real that you can’t hear. You spend time in the water with sharks and they can even detect the electrical heart, you know, the electrical current of the heartbeat of their prey. And just that, I think, fills you with so much wonder that you’re not going to crash and burn. And.

If we are gonna crash and burn, I’m gonna go down with a song of praise on my lips. It’s beautiful, thank you. Now there’s no topping that. We’re just gonna send courage your way, Howard. We’re just gonna send it for whatever you may need. There it is. You’re covered. My God.

Well, I am just so tickled that you both joined us. Howard, do you have something you want to add to that at all? I can’t really top that. I would just say you have to believe that quieter things, things of quality will prevail and will find the person who needs to hear them.

Well, thank you so much for coming and joining me on the porch. And I hope you’re here several more times this summer. Oh you bet. When you take a break for writing. Thanks so much. Thank you, Trish. Thank you. We love having you as our neighbor.

Sy and Howard are remarkable writers and neighbors. Sy makes a great pie and we renovated our house, Howard was right there with us, swinging a crowbar. After our visit, they left me thinking of a few questions:

- How do you honor the artists in your life? and how do you honor the artist in yourself?

- Are you creating dedicated time for your creative interests?

- And are there ways you can repurpose your work and reach a wider audience?

You can follow Sy on Instagram @sytheauthor and on Facebook @symontgomery

You can follow Howard on Instagram @howardmansfieldauthor and on Facebook @howardmansfield

And make sure to go to the show notes to check out the New England Emmy Award-winning documentary “A Journey to the White Mountains,” featuring the words of Howard Mansfield and the music of Ben Cosgrove and produced by our friends Liz and Matt Meyer Bolton of the Salt Project. To hear more about Liz and Matt’s work, listen to Season One, Episode Two!

If you’re listening to this podcast, it’s because you care about creativity and courage too. And believe like I do that this is no time to be timid. This year, I’m taking the no time to be timid message on the road and maybe your part of the world needs to hear it.

If you’re looking to awaken boldness and creativity in your company or organization, I’d love to come speak to you. Let’s have a conversation. Please reach out to me at booking @triciaroseburt .com.

Join us for our next episode — which is our last episode of Season Three if you can believe it! — when our guest will be writer R. Eric Thomas, and when I say writer, I mean a writer of the bestselling books, Congratulations the Best is Over and Here For It Or, How to Save Your Soul in America; award-winning plays like the recent “Army of Lovers,” and wildly popular columns, including his former column on Elle.com, “Eric Reads the News” and his just launched column “Asking Eric,” an advice column tackling life’s quandaries. And he’s a Moth storyteller and the long-running host of Philadelphia’s Moth StorySlam.

Believe me, you don’t want to miss this episode. In fact, you don’t want to miss any episodes, so make sure to subscribe to the show. And if you have any thoughts about the show we’d love to hear from you! So please out at podcast@triciaroseburt.com and remember, this is no time to be timid!

No Time to Be Timid is written and produced by me, Tricia Rose Burt. Our episodes are produced and scored by Adam Arnone of Echo Finch. And our theme music is Twist and Turns by the Paul Dunlea Group. If you like what you hear, please spread the word, subscribe to the show and review us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen. No Time to Be Timid is a presentation of I Will Be Good Productions.